At the end of 2016, a simple nick to my hand whilst playing with my dog would lead to a cascade of events that changed my life forever.

It began one afternoon at work. I had just seen my last patient when I started feeling as if I was getting the flu, that general unwell sensation of achy muscles, tiredness and feeling very cold. I went home, made a hot drink and got into bed, still shivering. I woke up the following morning, still feeling under the weather, and fell asleep again. I was home alone and getting sicker by the minute, without realising it. I vaguely remember that my phone rang several times, but I couldn't pick it up to answer. I also remember that I wanted to use the bathroom, but my legs and arms wouldn't work.

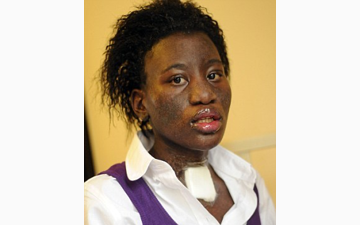

When my partner, Michael, got home that evening, I was very confused and disoriented. I could not have a meaningful conversation; I had slurred speech, I could not stand or walk, and my skin had turned blue and mottled. Michael later told me that I didn't know where I was and that I was argumentative and wouldn't let him call for an ambulance. Without me realising, I was delirious from a severe infection and close to dying.

The paramedics arrived quickly, and they immediately recognised the seriousness of the situation. They at once tried to stabilise me with intravenous fluids and oxygen, and they took me to A&E with flashing blue lights and sirens blazing. Later on, I developed post-traumatic stress disorder and seeing or hearing an ambulance triggered flashbacks of that evening.

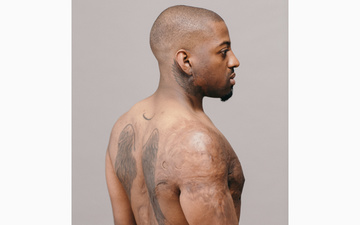

I collapsed in A&E; they took me to intensive care, where I was placed in an induced coma and on a ventilator. I was in septic shock, a condition where the body's immune response to an infection goes into overdrive. This reaction causes damage to internal organs, and blood clots develop, which block the blood supply to the limbs and soft tissue. It is a life-threatening situation with extremely high mortality.